Meet the invaders

A unique set of pests and weeds are invading the project area. Rabbits chew through the front country, hedgehogs, stoats and feral cats attack native species, and invasive weeds introduced by unsuspecting settlers compete with natives. We must act now before they change this special place forever.

Pests

Norway rats

How we are controlling rats?

Our extended trapping networks in the Tasman, Cass and Godley river valleys have increased the number of rats being trapped in the project area.

Unusually, rats are not as much of a problem in the Te Manahuna Aoraki project area as they are for other conservation projects.

There are no ship rats in the project area, but we do catch Norway rats in the wetlands and tarns of the Cass and Godley River valleys. Luckily the cold keeps rats away in large numbers, and the tussock dryland alpine environment is not to their liking.

However, the rats that do exist here are large enough to kill nesting braided river birds, and they eat rare native wētā, birds eggs, snails, frogs, and lizards. They are also partial to native flowers, fruit and seeds, which puts them in competition with native wildlife for food.

Photo : VJ Anderson Wikimedia Commons

Stoats

What are we doing to control them?

Te Manahuna Aoraki is actively trapping stoats, and we have a research project in the Malte Brun looking at whether stoats can be completely eliminated from a mountain site.

Stoats are deadly and relentless hunters who can travel large distances at great speed. They are the most widely detected predator in the project area and are regularly seen at altitudes of 2050m.

Our research has spotted one on a motion-activated camera at an altitude of 2135m but, given the lack of available prey at these heights, they are not at this altitude in large numbers.

Stoats don’t just kill to survive – they kill everything in sight and store surplus food for later. Their main prey are rats, mice, native birds, rabbits, hares, hedgehogs, possums, lizards and insects like wētā, so they have a significant impact on species in the project area, including tuke/rock wren, kea and ngutuparore/wrybill.

They are such a devastating predator because they can climb and swim, and they have good eyesight, hearing and a strong sense of smell. They also have big families. A female stoat can have up to 12 babies at a time, and a male stoat can impregnate baby females at only 2-3 weeks old – before they even open their eyes. Even though she is pregnant, her offspring aren’t born until the following spring when she is an adult.

Photos : Fight for the Wild credit Peter Young and trail cameras

Rabbits

What are we doing to control rabbits?

Te Manahuna Aoraki and our partners are targeting rabbits using a variety of methods, including aerial control and ground-based methods like patch poisoning using pindone, gassing burrows, trapping, and hunting using night-vision technology. Because rabbits are a tasty meal for pests like stoats, trapping of pests will be undertaken alongside rabbit control.

Rabbits are a major pest in the Mackenzie, through their direct impact on native vegetation and agricultural land, and because they are a food source for mammalian predators such as feral cats, ferrets and stoats. Higher pest numbers put native species at risk.

Rabbits eat their way through native vegetation and agricultural land, turning farmland into dustbowls riddled with burrows, where only weeds survive, and costing millions in lost production and control.

They don’t say ‘breeding like rabbits’ for nothing. Rabbits as young as five months’ old can have up to 50 babies a year and may be pregnant for 70% of a year. Eliminating rabbits, alongside predator control, will increase the survival of native birds, lizards, and bugs.

If we can sustain low rabbit numbers it will make a huge impact to the environment and support those land managers who already invest significant time and money to control rabbits.

Photos : Brian High, Robyn Janes, trail camera

Possums

How we are controlling possums?

A multi-species pest elimination trial in the Malte Brun will help us better understand how to most effectively target possums in remote high altitude sites.

The Australian brush-tailed possum is bad news for our forests and native species – stripping and killing trees, eating eggs and chicks, wētā and other insects.

Across New Zealand, it is estimated possums consume 21,000 tonnes of vegetation a night – that’s nearly the weight of Auckland’s Sky Tower every 24 hours. They are known to eat 70 types of native trees and can change the overall structure of a forest. Possums also compete with native birds for habitat and food and are the main source and carrier of bovine tuberculosis, or TB, a highly infectious and serious disease found in cattle and deer herds.

They were introduced to establish a fur trade, but with plenty of vegetation for food and no natural predators their numbers soared.

In the project area, our research has found a possum at 2070m – the highest a possum has been recorded anywhere. Normally they live at lower altitudes though, as there is a lack of tasty food higher up.

Research from Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) has found possums don’t like getting their feet wet, so rivers can be useful as a barrier to stop possums invading.

Photo : Fight for the Wild Peter Young

Hedgehogs

How we are controlling hedgehogs?

In 2021, the project began a trial to see whether it is possible to completely get rid of hedgehogs from 2300ha in the Mistake Valley. Another trial at a lower site at Paterson’s Terrace will help us plan how to eliminate hedgehogs across the entire project area.

Hedgehogs may look cute, but they are super-killers, eating chicks, eggs, lizards, skinks, wētā and other rare insects. They are also hosts to many parasites and diseases, various worms, fleas and mites.

They were first brought to New Zealand by Acclimitisation Societies. There are even reports of train drivers releasing crate-loads of the spiky pests on journeys through the South Island.

They thrived here, loving the New Zealand natives – a 2009 report in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology found a single hedgehog gut containing 283 wētā legs. Our monitoring of braided river birds like turiwhatu/banded dotterel has caught hedgehogs on trail cameras eating eggs from nests.

The project has attached GPS trackers and found them as high as 1937m in the mountains.

Given the high numbers of hedgehogs in the environment, they can have a huge impact on endangered species.

On a positive note, we have learnt hedgehogs have small home ranges, and tend to hunker down through winter at higher altitudes rather than move to warmer areas. This lack of seasonal movement means the populations are more stable and easier to manage, and once we get rid of them they are also slow to reinvade an area.

Photos : Nick Foster and Wikimedia Commons Karori Wildlife Sanctuary

Hares

What are we doing to control them?

Te Manahuna Aoraki has a trial site in the Malte Brun, where we are attempting to eliminate hares and other introduced predators. Results from this trial will help us understand how best to eliminate them from the entire project area.

Hares play a significant role in supporting populations of stoats and feral cats at higher elevations.

While they look like a rabbit, they are larger, with more powerful hind legs, which mean they can leap further than rabbits. They often zigzag wildly when chased.

Hares are solitary and can have huge home ranges up to 100ha. They are herbivores and their main ecological impact is damaging native vegetation and pasture. They will browse on sensitive alpine native species, even sharpening their teeth on vegetation. Hares can also compete with livestock for food, and two or three hares are said to eat as much as a sheep.

As they feed from sunset to midnight, hares tend to sleep during the day, in a shallow bowl made in long grass or under shrubs. Their main predators are feral cats, dogs or larger birds of prey.

Hares can have up to six litters each year, and the female has the unique ability to conceive the next litter while still carrying the first. They may live up to 12 years.

Ferrets

How we are controlling ferrets?

Te Manahuna Aoraki targets ferrets through trapping networks. Luckily they are one of the easiest species to reduce to low levels quickly, as they are inquisitive and not very trap shy.

Ferrets are common in the Mackenzie, particularly where rabbit numbers are high. They are usually found between 1500-1750m although they have been spotted at 1731m in the project area – the highest know record of a ferret.

While rabbits are their main diet, when there is a sudden reduction in rabbit numbers, hungry ferrets look for other food, like native birds, lizards, wētā, even rodents. They also threaten the farming industry as, similar to possums, they can carry bovine tuberculosis (TB).

Larger and stockier than stoats, ferrets are the largest mustelid found in New Zealand and were introduced from Europe. They have played a role in the decline of native birds like kakī, kiwi, whio and tūtiriwhatu/banded dotterel.

Ferrets are mainly nocturnal, with an average home range in the Mackenzie Basin of 150ha depending on food supply. Males can range up to 288ha and females 111ha. They breed in spring and can have up to 12 young.

Photo Tom Smits, Ryan Hagerty via Wikimedia Commons

Feral cats

How we are controlling feral cats?

Feral cats are intelligent animals, so they are hard to control and trap. The project is targeting them through trapping, toxins, using motion-activated cameras and tracking with conservation dogs. We are also planning to GPS track feral cats to understand where they range and whether they will cross the canal – if not we could use these waterways as a barrier to stop reinvasion.

Feral cats are the top predator in Te Manahuna. They love to hunt and live in the wild with little to no human contact.

While they look similar to domestic cats, they grow to a much larger size. They have tough, short lives and can travel long distances. Scientists have tracked a feral cat cat in the high country that covered almost six kilometres in one night.

Even if they are well-fed, feral cats are driven to hunt, and they are built for it. They can see in low light and can hear the ultrasonic calls of rodents. Braided river birds are extremely vulnerable, as are native lizards and bugs and alpine birds like tuke/rock wren.

In the project area, feral cats tend to prefer the lower regions because of the abundance of rabbits, but they have been spotted on the Malte Brun range. GPS tracking shown they go to higher elevations in winter presumably to hunt hares when rabbit numbers are low.

Canada geese

How we are controlling canada geese?

To improve the habitat of threatened native species, and water quality in lakes like Lake Alexandrina, The Te Manahuna Aoraki project, in collaboration with DOC and LINZ are assisting farmers in the area to humanely control geese in an efficient and co-ordinated way.

Te Manahuna Aoraki are attaching GPS radio collars to Canada geese to track their movements over an 18-month period. This will help determine how effective culls are, and provide information about where the geese move to, so we can work with other runholders across the Mackenzie Basin to humanely reduce geese numbers across the region.

Canada geese are a major problem in the Mackenzie Basin as they significantly impact native and exotic grasslands, and destroy the habitat of threatened native species like kakī/black stilt and crested grebe.

Large flocks of Canada geese damage pastures and pollute waterways like freshwater springs, wetlands, lakes and tarns with their droppings. They also impact farmers by eating large amounts of pasture and crops. It is estimated that four to five geese eat the same amount of grass as one sheep.

Introduced from North America, they live on high country waterways in summer before heading to breeding grounds in the headwater valleys of rivers flowing from the Southern Alps in spring.

Photo : Wikimedia Commons Joe Ravi

Black-backed gull/karoro

How we are controlling black-backed gulls?

Te Manahuna Aoraki plans to reduce black-backed gull populations to more naturally low levels, of less than 20 pairs.

The black-backed gull is one of only two native bird species not given any level of protection under the Wildlife Act. That’s because it is a very aggressive hunter, pirate, and scavenger that predates on braided river birds like black-fronted tern/tarapirohe, black-billed gull/tarāpuka, wrybill/ngutu pare, and banded dotterel/tūturiwhatu.

Black-backed gulls form large colonies, and are opportunistic feeders. As well as river birds, they take a wide variety of foods including offal, refuse, marine invertebrates, shellfish, fish, frogs, lizards, small fruit and other plant material.

The number of black-billed gulls in the project area is artificially high because so many agricultural food sources are available.

Photo : Department of Conservation trail cam

Weeds

Willow

How we are dealing with this pest species?

We are targetting willows in key biodiversity areas like braided rivers and wetlands where they compete vigorously with native species and change the course of waterways. There are about six different species of willows but we are mainly eliminating grey willow, and crack willow.

Willows absorb water and were introduced here from Europe to help control rivers and streams. They are often planted to stabilise river banks and provide shelter and shade, however in the wrong place they can spread quickly and take over.

The willow trees grow rapidly and spread through waterways, creating dense thickets and competing with natives as well as causing blockages and flooding. Seeds are spread by the wind and stem fragments are spread via water.

They are deciduous and can grow to around 7m high. They produce catkins, or flowers, from September to October and willow seed capsules contain lots of seeds. Willows tolerate all sorts of conditions including flooding and hot and cold temperatures, which means they do well in the Mackenzie Basin.

Gorse

How we are dealing with this pest species?

The project aims to eliminate all adult gorse plants by 2024. We are spraying the gorse and will then continue to monitor gorse hot spots to deal with new seedings.

Gorse is another species that was brought here from Europe by unknowing settlers in the 1800s. It was used as hedgerows and fodder but thrived in New Zealand’s temperate climate.

With its spiny woody stems, and yellow flowers that appear twice a year it is easily recognised. Given the chance, it vigorously colonises open ground near river systems, right up to the lower slopes of mountains, preventing the growth of native seedlings and increasing nitrogen in soil, which can make it hard for natives to establish in some circumstances. The woody stems can also be a fire hazard.

Gorse isn’t all bad though and can act as a nursery crop to help with native bush regeneration. While young gorse plants can some stop some species of natives growing, gorse becomes leggy as it gets older and provides ideal conditions for natives seeds to germinate and grow under. The natives grow up through the gorse, eventually cutting out its light and replacing it.

It is a hard weed to get rid of as seed can actually lie dormant for over 100 years germinating after the adult plants have been removed. Unfortunately most methods of removing adult gorse plants such us bulldozing or burning create the ideal conditions for the gorse seeds to germinate.

Cotoneaster

How we are dealing with this pest species?

The project is aiming to eliminate 90% of adult plants by 2024 using LINZ Jobs for Nature funding.

Cotoneaster is another plant that was popular with early settlers, and was planted widely in areas where people once lived and worked.

An evergreen shrub, originating in the Chinese Himalayas, it can grow 1-3m high. It’s small white/pink flowers are followed by bunches of scarlet berries.

Cotoneaster produces large amounts of seed, matures quickly and is very long-lived. That is bad news for native species, particularly shrublands, as it out-competes them and forms dense stands which crowd out the natives. It is also very tolerant of hot and cold temperatures which means it does well in the project area.

Flowering cherry

How we are dealing with this pest species?

LINZ Jobs for Nature funding has seen the biggest effort in 20 years to control flowering cherry. In 2021, 4481 flowering cherry plants were targeted in the national park. The aim is to eliminate all adult plants by 2024.

Flowering cherry has spread from gardens planted by settlers near Mount Cook Village before it became a national park.

Aoraki Mount Cook National Park is the site of the worst infestation in the project area, with thousands of flowering cherry spreading throughout native shrublands near the village. It is a tree that can form forests which overtop and suppress native species so there is a risk it will completely alter the look of the area, shading out the native woody vegetation.

Flowering cherry also grow around twice as fast as native shrubs and reproduce fast.

If not controlled it was thought it could spread as far as the moraines of the Tasman and Mueller Glaciers’ over 30-50 years.

Photos Robyn Janes, Peter Willemse

Wilding conifers

How we are dealing with this pest species?

Te Manahuna Aoraki supports the work all parties are doing to control wildings as it allows us to focus on controlling other weed species.

The Mackenzie Basin has been called ‘ground zero’ for the battle against wilding conifers.

Wilding conifers are trees that spring up where they’re not wanted, and quickly take over a landscape. In Te Manahuna, pines like Douglas fir and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), have spread from trees planted by earlier government departments, to stop erosion, enhance the landscape and provide shelter.

The problem is one tree can produce thousands of seeds and when these seeds are blown by strong winds, they can be carried kilometres away. From the early plantings, wildings have quickly got out of control, drastically changing the tussock landscape.

Wilding conifers cause many problems. They grow much faster than native trees so plants like mountain flax and coprosma – which provide berries and nectar for native birds – don’t grow. Blankets of pine needles suppress native tussocks so butterflies, wētā, grasshoppers, lizards and other native species also lose their habitat.

They severely impact farmers by quickly taking over productive land. Wildings also need large amounts of water to grow, so less water reaches the streams and lakes, impacting on native fish populations and recreational activities like fishing and boating.

Te Manahuna landowners have been trying to get rid of wilding conifers for decades, and many are members of Wilding Free Mackenzie, a charitable trust working to deal with the challenges of wildings. A number of agencies are also working together to control them including DOC, LINZ, MBIE, ECan, and the National Wilding Conifer Control Programme.

Photos Dave Kwant

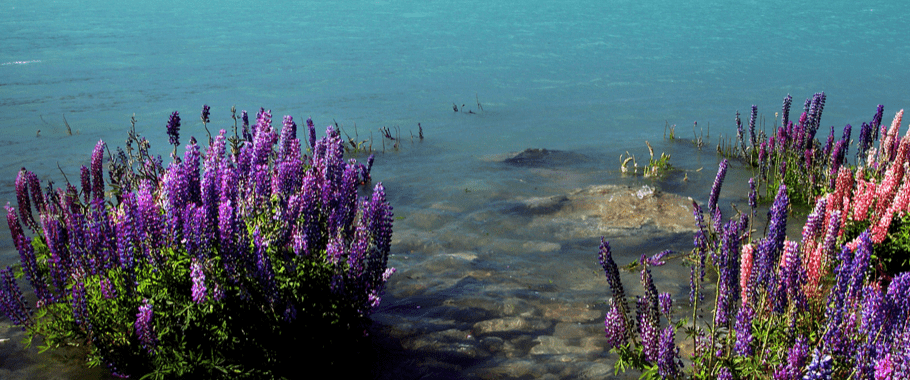

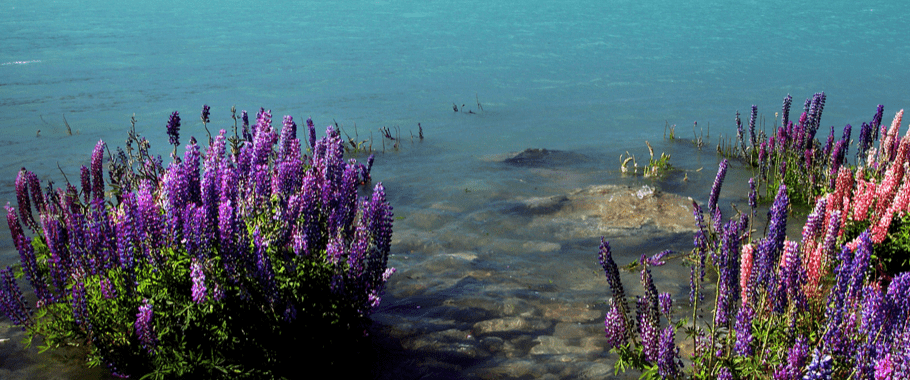

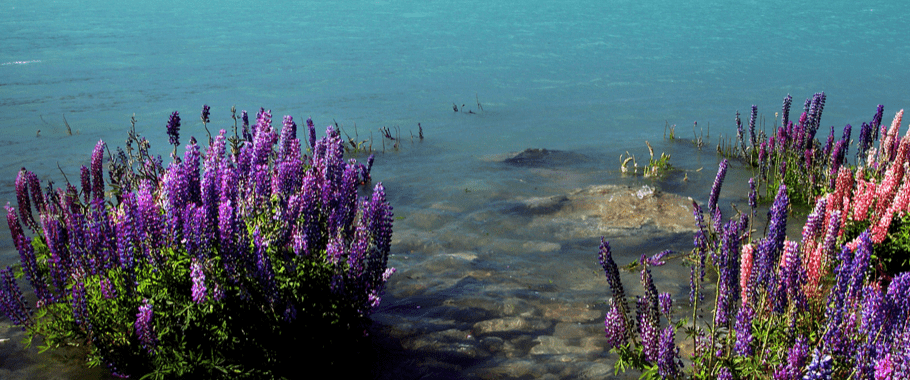

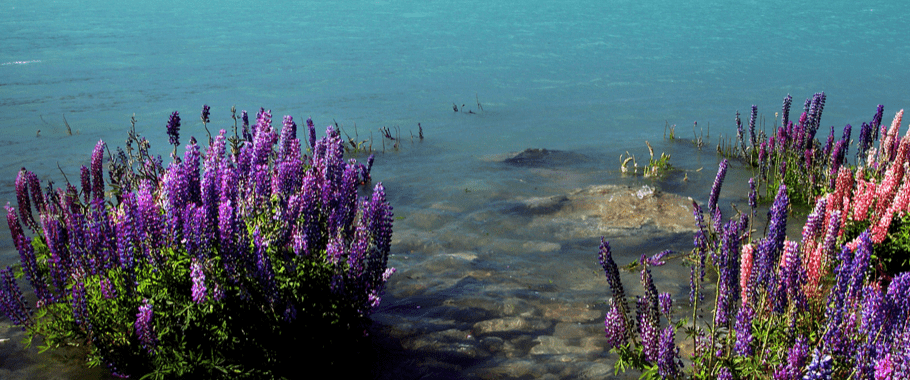

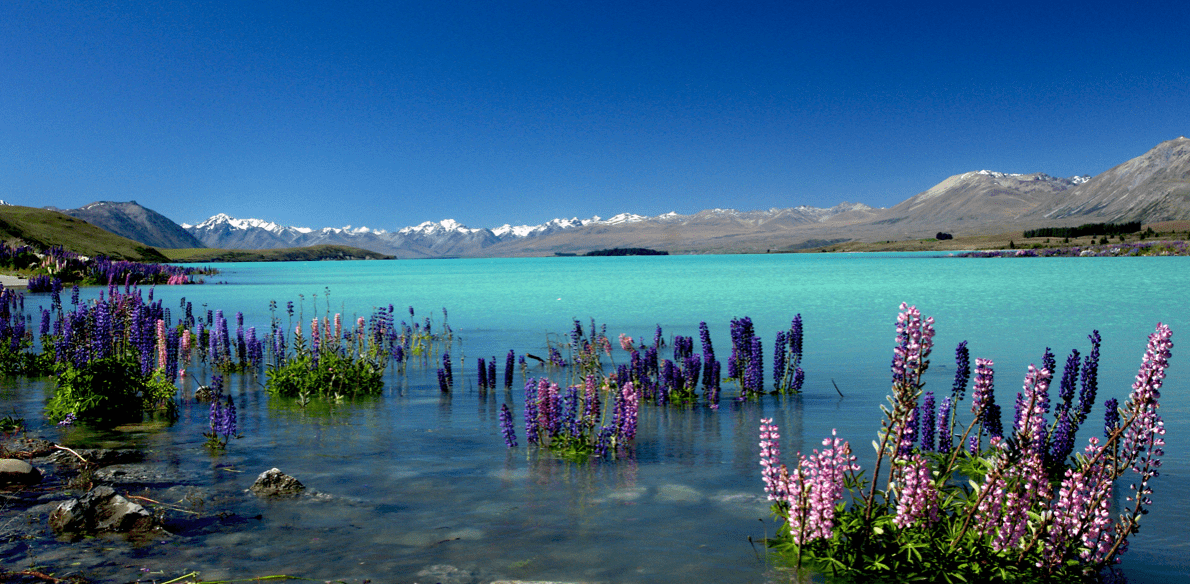

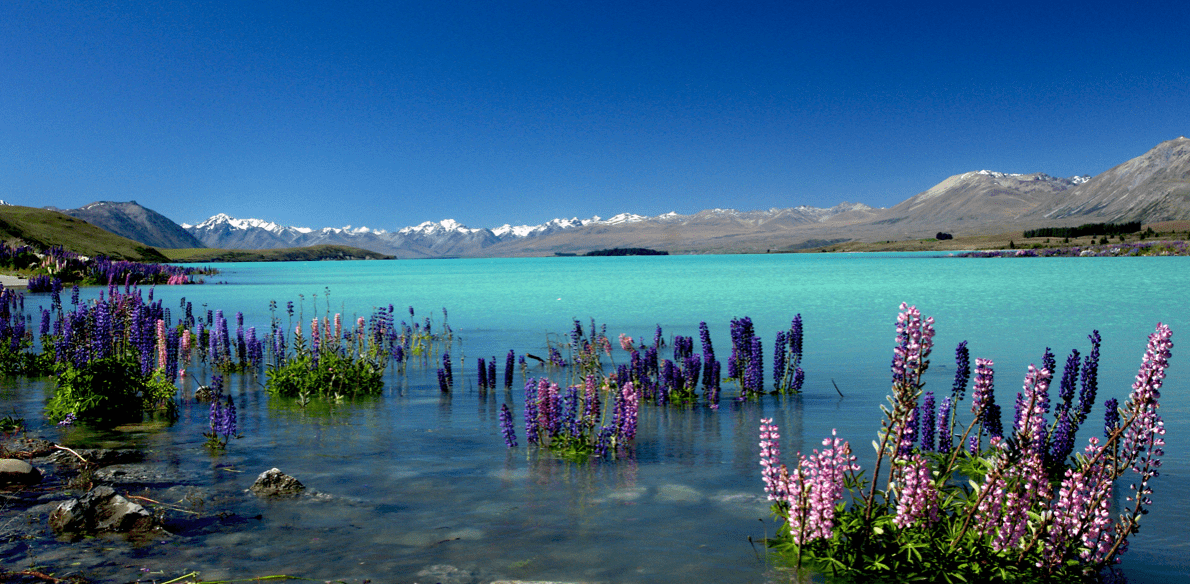

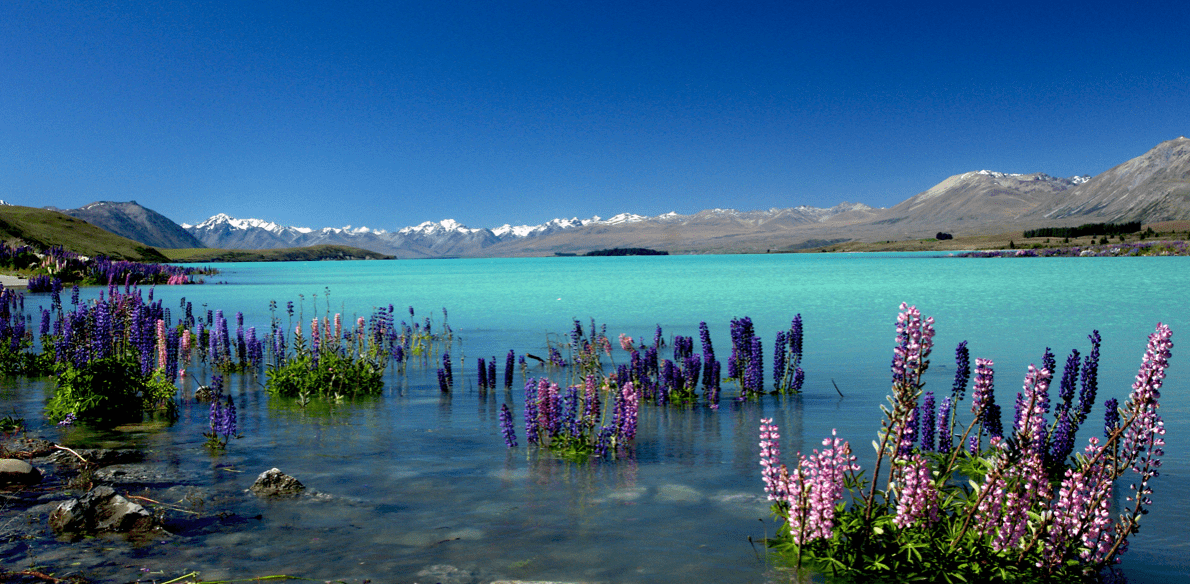

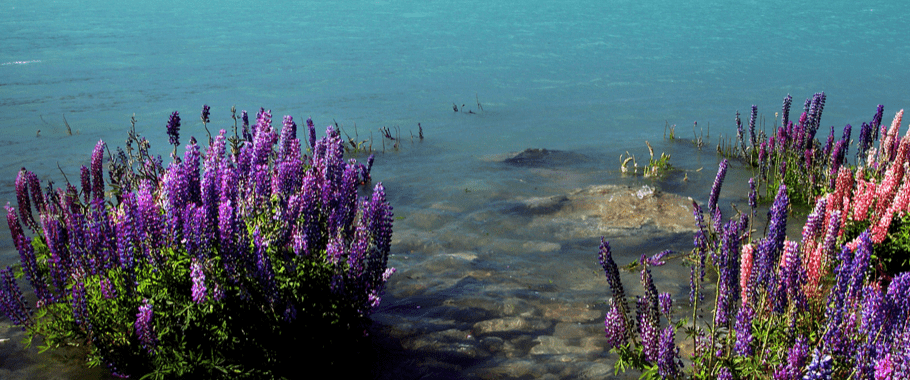

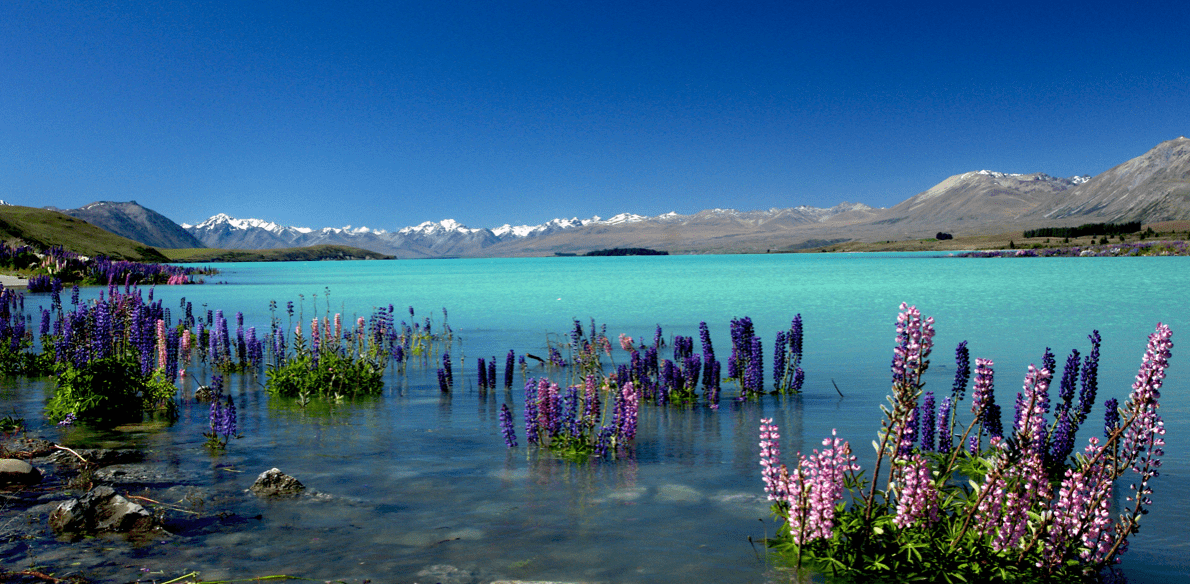

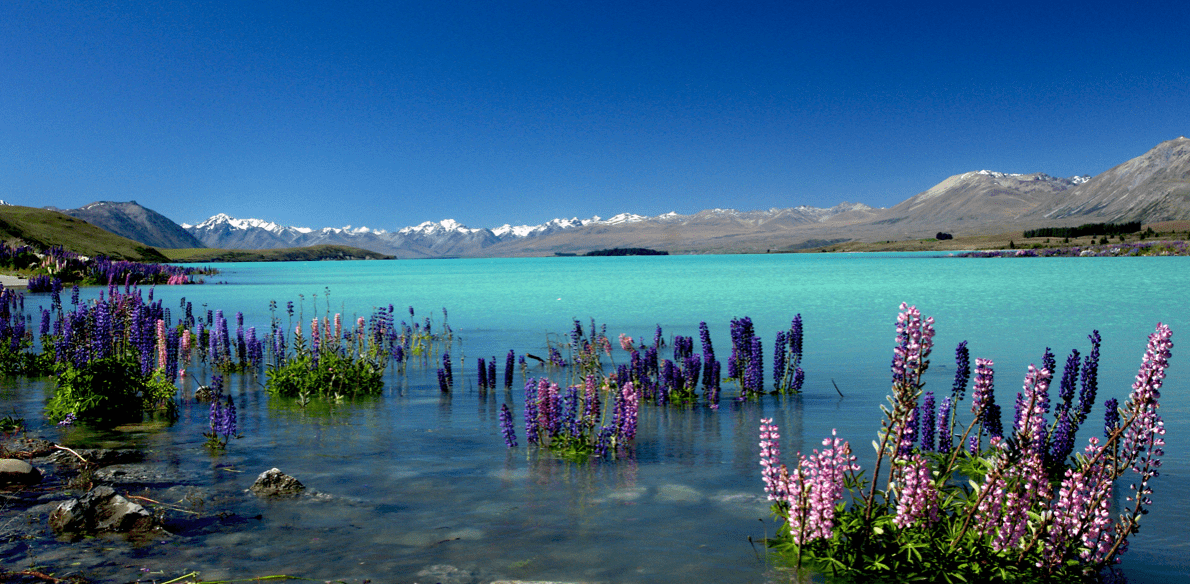

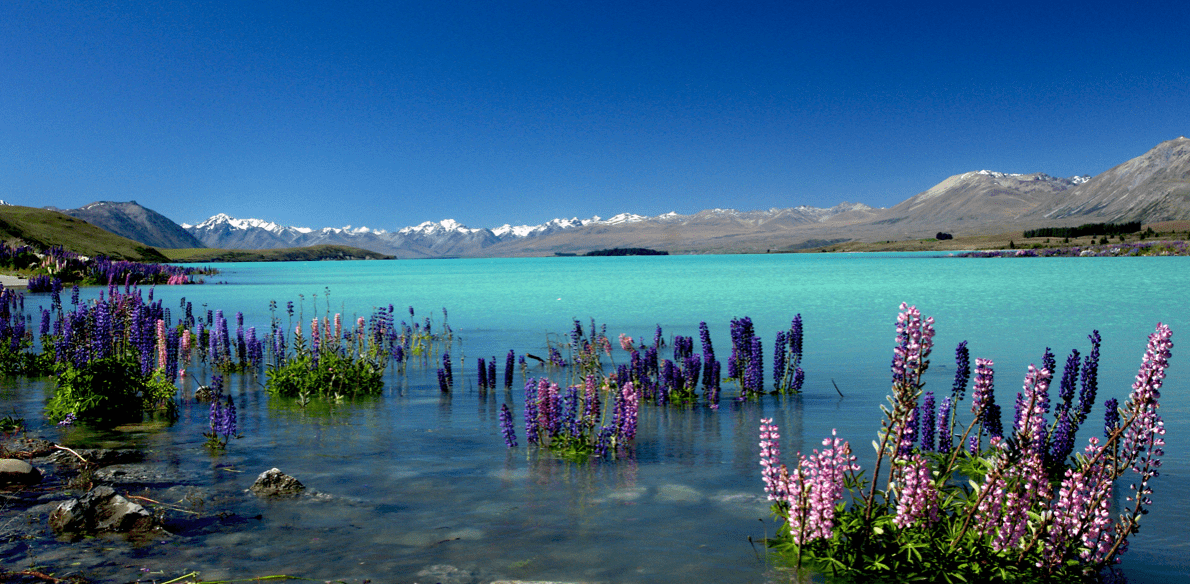

Russell lupin

How are we controlling this invasive weed?

The project is reducing lupin numbers to zero in biodiversity hotspots like braided riverbeds, and Aoraki Mount Cook National Park.

Popular spots to photograph lupins by Lake Takapō/Tekapo are not being targeted.

Russell lupins in the Mackenzie Basin are a perfect example of a garden plant in the wrong place.

A native of North America, their colourful flowers are much photographed by visitors during summer. However, in New Zealand Russell lupins are aggressive weeds that if left unchecked will choke out natives in unwanted locations like braided rivers, tussock grasslands and wetland habitats.

These areas are home to threatened species like kakī/black stilts, ngutu pare/wrybill and turiwhatu/banded dotterel. Lupins can grow to 1.5m tall, and not only do they invade the habitat of these birds, but they also provide cover for predators. Lupins encroach on the native birds’ nesting habitat, and capture silt which changes the course of braided rivers.

Photos : Robyn Janes and Peter Willemse

Rowan

How are we getting rid of it?

Te Manahuna Aoraki is collaborating with DOC, landowners and Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) to reduce rowan infestations.

The aim is to completely remove adult rowan from the project area by 2024, with a particular focus from National Park to Boundary Stream on the Ben Ohau Range.

We are using aerial spot spray control and ground based contractors to cut trees and treat stumps.

Rowan trees are garden escapees that compete for space with our native plants.

In ancient times, this woody tree was planted to ward off witches, but it’s more likely European settlers planted this species in homestead gardens and travellers rests to remind them of home.

Rowan’s bright red berries are easily spread by birds and the plant thrives in the project area. If left unchecked, rowan could become another wilding pine problem, spreading out of control in the tussock and shrublands.

Photos : Peter Willemse, Robyn Janes

Broom

How are we controlling broom?

As the broom seedbank lasts for over 90 years, we are building on initial work by DOC to trial bio-control methods for the long-term benefit.

In 2019, different bio-control agents, including broom seed beetles, broom gall mites and broom psyllids were trialled. These bugs each weaken a different part of the broom plant, reducing its vigour and seeding.

Broom, is a scrawny shrub that multiplies quickly, competing with natives and rapidly changing the landscape.

It’s explosive seed mechanism spreads seeds up to 1.5m from the parent plant. They are easily caught in animal fur, and wind can blow them even further, so broom can quickly colonise braided riverbanks and tussock grassland areas. Broom is also a legume that fixes nitrogen in the soil, disturbing the ecology of an area by changing the type of plants that can survive where it has been growing.

There are two main infestations in the project area, at Jollie River and Takapō’s Boundary Stream, an area of approximately 230 ha. That means we have the opportunity to deal to it before it spreads out of control.

Photos : Phil Tisch, Peter Willemse

Our Work

Find out more about our work to protect native species

Report a sighting

We’d love to know what you’ve seen in the area – email us now

Photo credits: